Words: Alice Cavanagh

Photos: Alice Gao

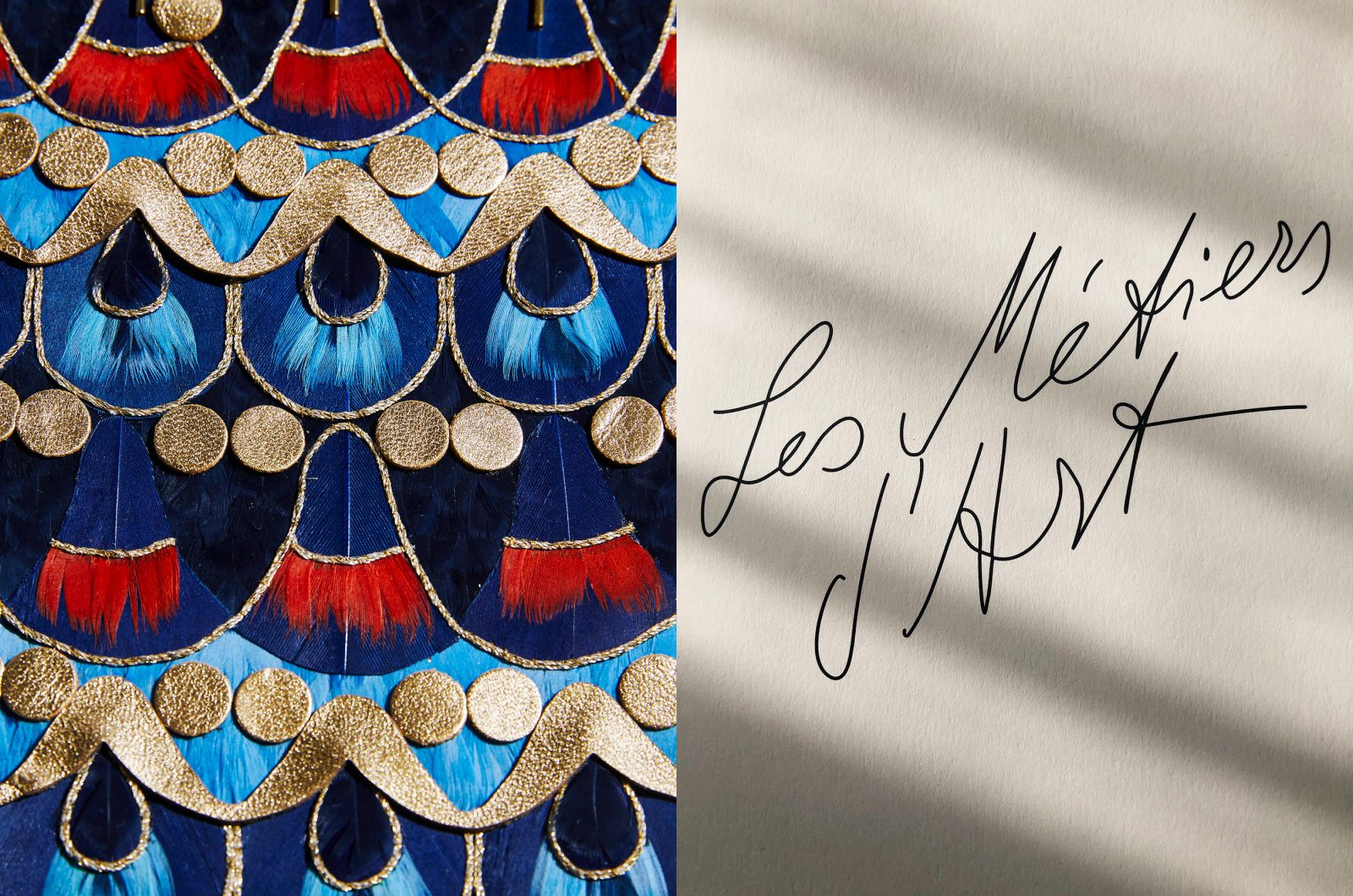

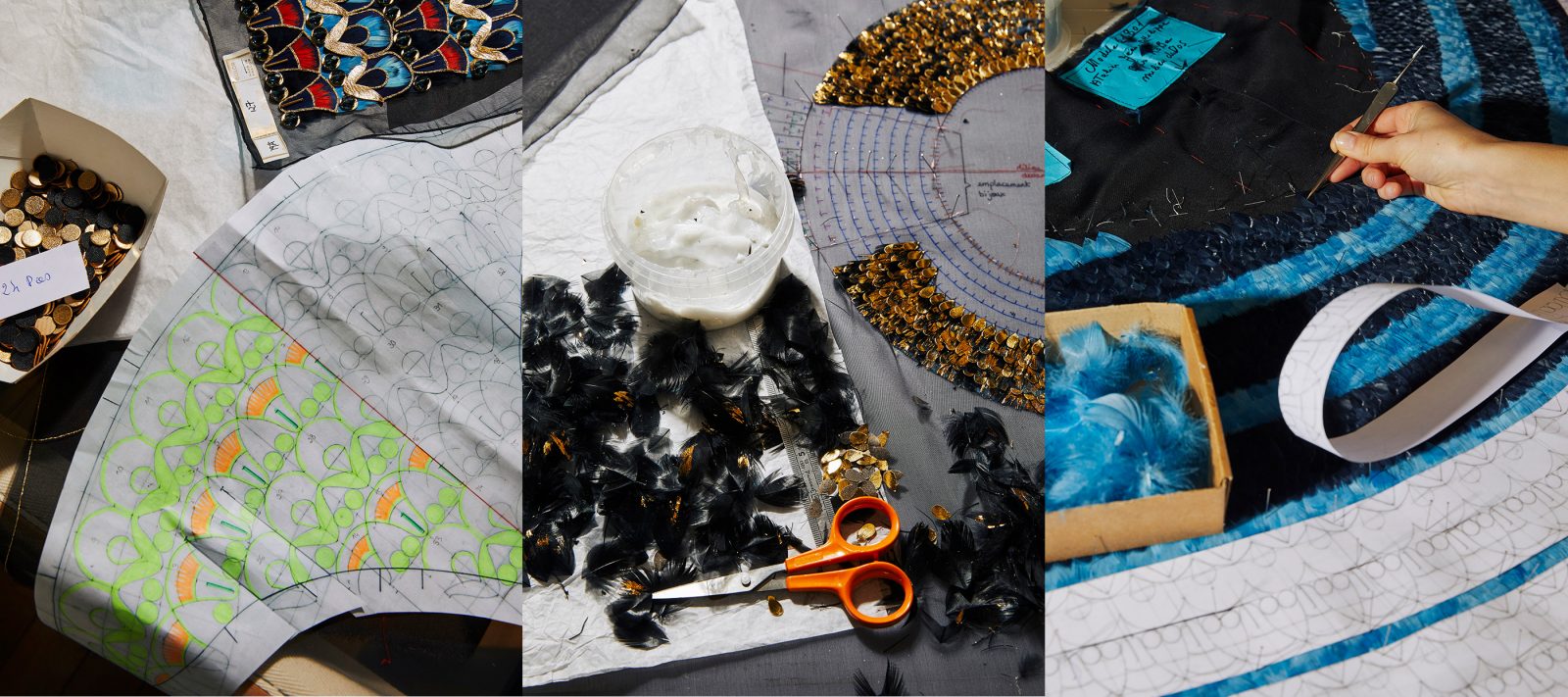

It’s one week out from the Paris-New York Chanel Métiers d’Art show, and ten artisans in the feather house of Lemarié in Paris have their heads bowed together, diligently gluing brilliantly coloured feathers onto the skirt of a dress. They work in tandem, fashioning a bold zigzag pattern across a stretch of fabric that spans the surface of a table. It takes hundreds and hundreds of hours to complete this one style: each feather has been dyed and then carefully cut and arranged by hand. From afar, the feathers glisten in the light like paint and — much like a great work of art — up close you can see an extraordinary deftness of hand.

In another room, feathers are being embroidered onto fabric in a graphic motif that looks like the plumage of a mythical bird or the pattern on a majestic headdress. The room hums with women of all ages. This is a storied practice that has been passed down over multiple generations — Lemarié can trace its roots back to 1880 and Chanel has been a part of that story for nearly 70 years.

The rich traditions and technical savoir-faire of such specialty houses have long been an essential part of the craft of haute couture but since the advent of industrialization, this art form — creative expertise, fashioned by hand — has dwindled. Houses like Lemarié, of which there were once 300 in Paris alone, are now in the single digits.

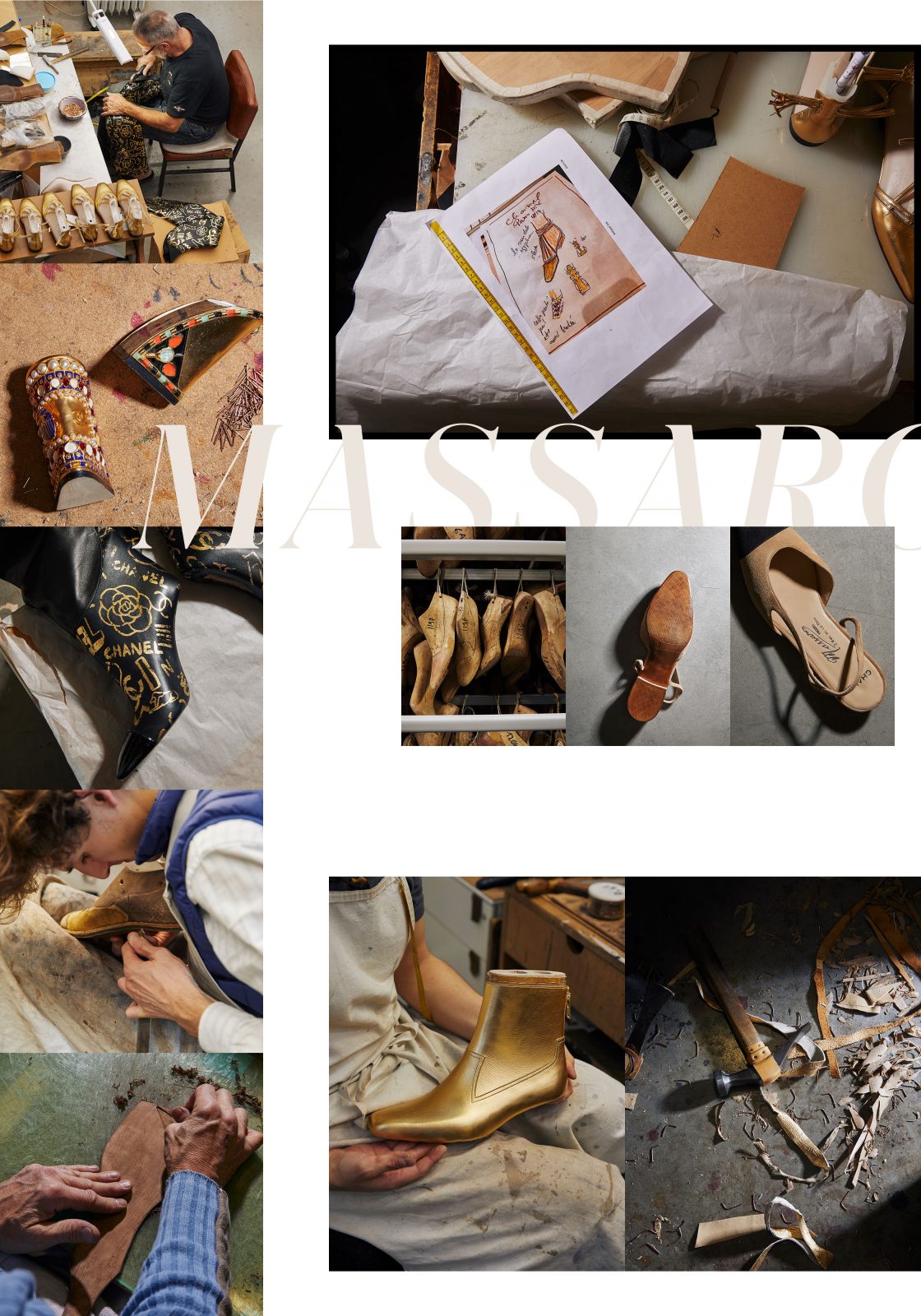

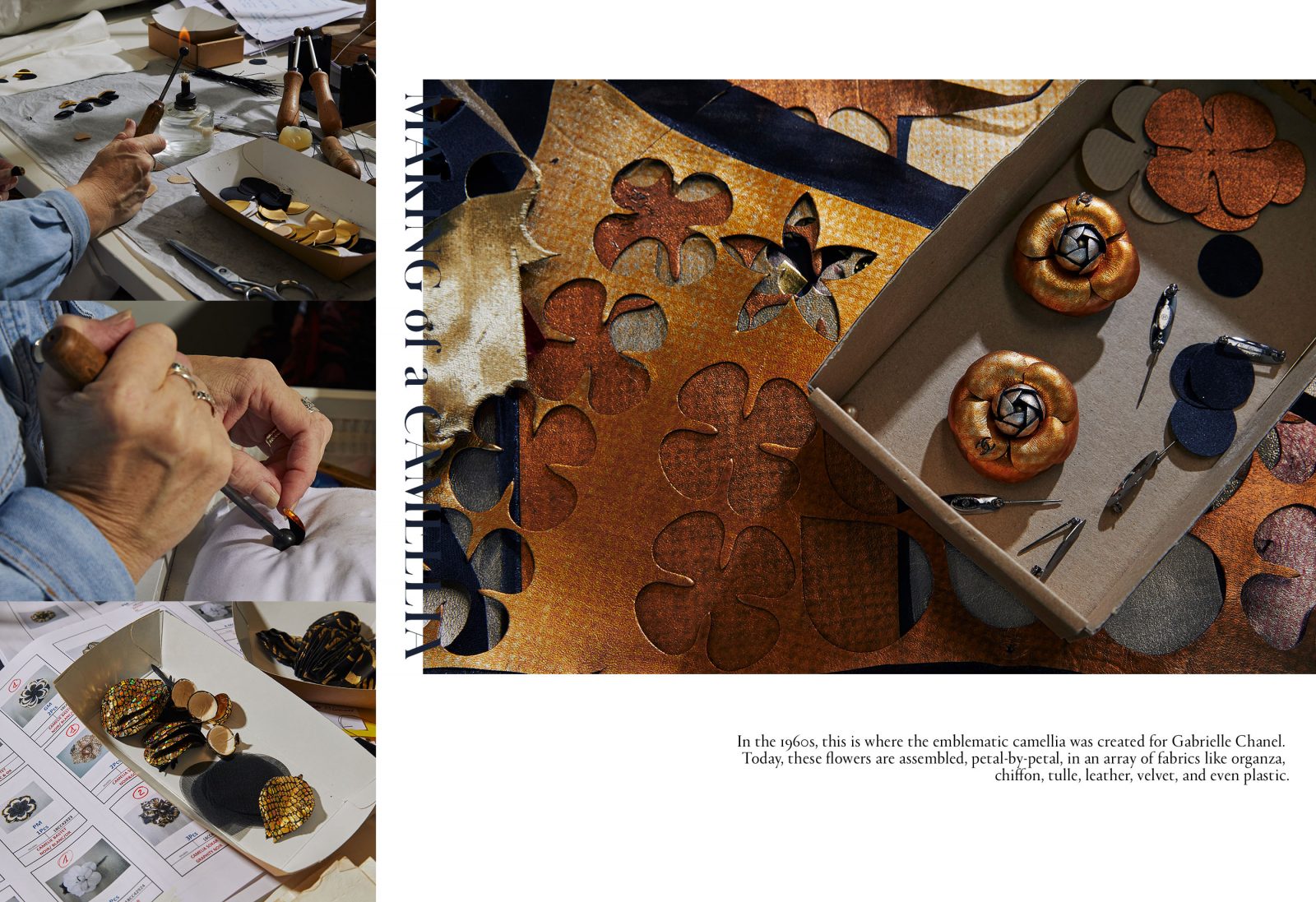

Chanel, for their part, has gone a long way in preserving such traditions and the livelihoods of these artisans by creating a subsidiary group that now safeguards almost two-dozen of these workshops. Along with Lemarié, there is the hat maker Maison Michel, the bootmaker Massaro, the pleating specialists of Lognon and other embroidery houses like Lesage and Montex. Collectively, they have the skillset to custom-make everything from gold buttons to straw boaters, and they do.

Every December, Karl Lagerfeld presents a Métiers d’Art collection that celebrates and showcases the prowess of these industries. The collection serves as a vital example of how an investment in time and talent can produce truly astonishing garments. It is a necessary antidote to the fast and the throwaway. More than just a workshop, however, these Houses boast a creative pulse, and these Métiers d’Art collections are a collaborative effort between Lagerfeld and the creative directors of each house. The process often begins with the Chanel artistic director offering either an abstract reference or detailed illustrations, with an open invitation to interpret aspects of the collection in the manner that inspires them most.

For the Paris-New York collection, for example, the embroidery house of Lesage drew inspiration from the Ancient Egyptians and precious relics of the antiquities. This played out in the vibrant, mineral colour palette that was used on a motif that resembled the palms of a papyrus leaf. Employing the Luneville hook, each individual thread is a precious embellishment in its own right. Other embroideries in the collection featured heavy stones and bugle beads that boldly decorated the straps and bodices of dresses. Lesage is one of the largest in the group with a booming business that sees them working with many of the biggest fashion houses in Paris. The archive here is like a treasure trove of 20th Century fashion — there are over 70,000 embroideries housed here. For more than a decade, designers come to here for a touch of the avant-garde. For Chanel, Lesage also develops hand-loomed tweeds in brilliant hues.

Offering a more subtle interpretation of the Paris-New York collection theme, the House of Lognon developed a fine, 5mm-wide accordion pleat that added flair to the skirts and sleeves of several styles. Lognon can trace their roots back to the time of Napoleon III and boasts an archive brimming with hundreds of original cardboard molds — all original and all created by hand. There is a fine art to pleating and, to make each form, the designer first traces a motif by hand onto the cardboard and then carefully folds along each line. Fabrics are then pressed into these cardboard molds and set with weights then steamed before they spring to life on garments.

Pleating is an essential part of Chanel’s DNA, but the two-tone pump, developed for Gabrielle Chanel by the master bookmaker Massaro in 1957, is one of the ultimate calling cards. (Fun fact: the ingenious design of the black toecap offers the optical illusion of shrinking the wearer’s foot.) For the Paris-New York Métiers d’Art collection, the two-tone pump was reimagined in decadent gold leather, as were a procession of knee-high boots. In a masterful collaboration with the jewellery houses of Goossens and Desrues, some of the heels were adorned with resin, pearls and gems. Such precious touches are the signature of these ateliers — long may they continue to thrive.